Introduction

Abbreviations

| AoG | All-of-government |

| CIMS | Coordinated Incident Management System |

| CTAG | Combined Threat Assessment Group |

| DPMC | Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet |

| HRB | Hazard Risk Board |

| NAB | National Assessments Bureau (DPMC) |

| NCMC | National Crisis Management Centre |

| NSC | Cabinet National Security Committee |

| NSS | National Security System |

| NSSD | National Security System Directorate (DPMC) |

| ODESC | Officials' Committee for Domestic and External Security Coordination |

| ODESC(G) | Officials' Committee for Domestic and External Security Coordination (Governance) |

| SIB | Security and Intelligence Board |

| SitRep | Situation report |

| SPOC | Single point of contact |

| SRRP | Security Risk and Resilience Panel |

| TAG | Technical Advisory Group |

Purpose

This handbook sets out New Zealand’s arrangements with respect to both to the governance of national security and in response to a potential, emerging or actual national security crisis. It is divided into four sections:

- Part 1: The National Security System;

- Part 2: National security governance structures;

- Part 3: Response to a potential, emerging or actual event;

- Part 4: Supporting annexes.

Audience

The intended audience of this handbook is officials from New Zealand’s National Security System in its broadest sense, specifically:

- Chief Executives who are likely to be involved in the Officials’ Committee for Domestic and External Security Coordination (ODESC);

- Hazard Risk Board (HRB) and Security and Intelligence Board (SIB) members;

- Senior officials who will be involved in Watch Groups, Working Groups, Specialist Groups or other committees;

- Officials who brief senior officials or Chief Executives;

- Officials involved in committees and groups;

- Controllers and Response Managers1 who may be involved in a nationally significant event;

- Recovery Managers who may be involved in a nationally significant event.

1 The terms “Controller” and “Response Manager” are defined in the Coordinated Incident Management System (CIMS) and refer to response activities carried out by individual agencies.

Part 1: The National Security System

Introduction

- One of the most important responsibilities of any government is to ensure the security and territorial integrity of the nation, including protecting the institutions that sustain confidence, good governance, and prosperity.

- In order that this responsibility can be discharged, a government requires a resilient national security machinery – which is well led, strategically focused, coordinated, cost-effective, accountable, geared to risk management, and responsive to any challenges that arise.

- The architecture described in this handbook provides the platform for the management and governance of New Zealand’s national security. Its effective functioning underpins New Zealand’s ability to maintain a secure and resilient country.

- The New Zealand Government’s responsibility for national security involves balancing many competing interests, including short-term and long-term, domestic and external, public and private, and financial and non-financial. To help the Government strike an appropriate balance between these various interests, the following principles are observed:

- The National Security System should address all significant risks to New Zealanders and the nation, so that people can live confidently and have opportunities to advance their way of life;

- National security goals should be pursued in an accountable way, which meets the Government’s responsibility to protect New Zealand, its people, and its interests, while respecting civil liberties and the rule of law;

- Decisions should be taken at the lowest appropriate level, with coordination at the highest necessary level. Ordinarily those closest to the risk are best able to manage it;

- New Zealand should strive to maintain independent control of its own security, while acknowledging that it also benefits from norms of international law and state behaviour which are consistent with our values, global and regional stability, and the support and goodwill of our partners and friends.

What is national security?

- National security is the condition which permits the citizens of a state to go about their daily business confidently free from fear and able to make the most of opportunities to advance their way of life. It encompasses the preparedness, protection and preservation of people, and of property and information, both tangible and intangible.

- New Zealand takes an “all hazards – all risks” approach to national security, and has done so explicitly since a Cabinet decision to this effect in 2001.2 This approach acknowledges New Zealand’s particular exposure to a variety of hazards as well as traditional security threats, any of which could significantly disrupt the conditions required for a secure and prosperous nation. National security considerations for New Zealand include state and armed conflict, transnational organised crime, cyber security incidents, natural hazards, biosecurity events and pandemics.

- The New Zealand system also emphasises the importance of resilience, which is the ability of a system to respond and recover from an event (whether potential or actual). Resilience includes those inherent conditions that allow a system to absorb impacts and cope with an event, as well as post-event adaptive processes that facilitate the ability of the system to reorganise, change, and learn from the experience. It means that systems, people, institutions, physical infrastructure, and communities are able to anticipate risk, limit impacts, cope with the effects, and adapt or even thrive in the face of change.

- To achieve this, New Zealand takes a holistic and integrated approach to managing national security risk.

Known as the 4Rs this encompasses:- Reduction — identifying and analysing long-term risks and taking steps to eliminate these risks if practicable, or if not, to reduce their likelihood and the magnitude of their impact;

- Readiness — developing operational systems and capabilities before an emergency happens;

- Response — taking action immediately before, during or directly after a significant event;

- Recovery — using coordinated efforts and processes to bring about immediate, medium-term, and long-term regeneration.

- Managing national security risk and supporting the country’s resilience is complex and involves a wide range of government agencies. These agencies work together to address the multidimensional and multidisciplinary nature of the threats and hazards. Local government, quasi-government agencies and the private sector also have increasingly important roles within national security. Effective coordination of effort, particularly of our strategic direction and communication activity, is very important.

2 POL Min (01)33/18.

Objectives

- Seven key objectives underpin the comprehensive “all hazards” approach that the New Zealand system

takes to national security:3- Ensuring public safety — providing for, and mitigating risks to, the safety of citizens and communities (all hazards and threats, whether natural or man-made);

- Preserving sovereignty and territorial integrity — protecting the physical security of citizens, and exercising control over territory consistent with national sovereignty;

- Protecting lines of communication — these are both physical and virtual and allow New Zealand to communicate, trade and engage globally;

- Strengthening international order to promote security — contributing to the development of a rules-based international system, and engaging in targeted interventions offshore to protect New Zealand’s interests;

- Sustaining economic prosperity — maintaining and advancing the economic wellbeing of individuals, families, businesses and communities;

- Maintaining democratic institutions and national values — preventing activities aimed at undermining or overturning government institutions, principles and values that underpin New Zealand society;

- Protecting the natural environment — contributing to the preservation and stewardship of New Zealand’s natural and physical environment.

3 DES Min (11)1/1.

Principles

New Zealand's strategic security environment

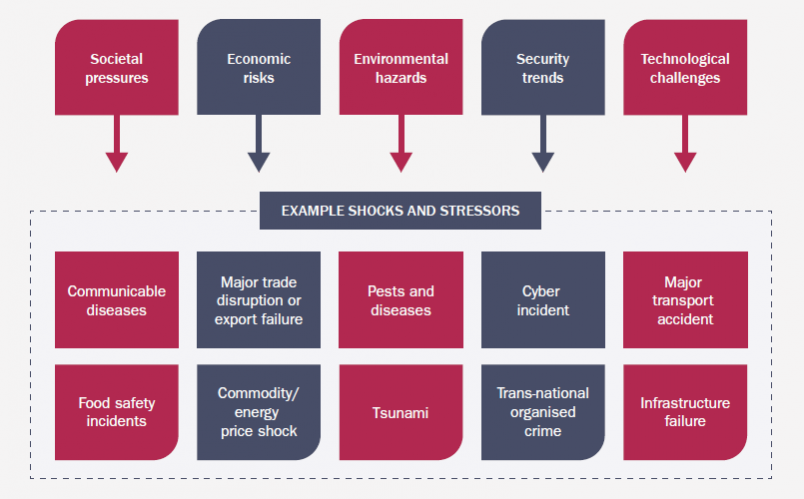

Risk drivers in New Zealand’s strategic securityenvironment

Figure 1. Risk drivers in New Zealand’s strategic security environment

- As discussed in paragraph 6, New Zealand conceptualises its national security settings on an “all-hazards” basis. This means that all risks to national security whether internal or external, human or natural, are included within the ambit of the national security structures. This is an important point: “national security” in the New Zealand context encompasses more than the traditional definition of security as solely the preserve of defence, law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

- Taking such a broad approach to risk identification and risk response requires a flexible and adaptable national security architecture. New Zealand’s capacity to deal with the full range of national security challenges requires the system to be integrated, able to leverage partnerships between government agencies, local government, private companies, and individuals.

Role of central government

- Central government bears the main responsibility for New Zealand’s national security. This is due to a combination of its primary responsibility for international relations, its ability to direct civil and military assets, the technical and operational capacity and capability at its disposal, its ability to legislate or appropriate substantial funding with urgency, as well as its ability to direct the coordination of activity when necessary.

- This central government role involves an agency, or a group of agencies, protecting New Zealand through the delivery of core, business-as-usual services, (eg, border management and protection services delivered by the Ministry for Primary Industries, New Zealand Customs Service, Aviation Security Service, and New Zealand Police). In other situations, it involves multiple agencies acting together to respond to an emerging threat (eg, serious political instability in the Pacific) or in response to an emergency (eg, a major earthquake). In all cases, it involves maintaining and investing in institutional risk reduction, readiness, response and recovery capabilities that are integrated and aligned across agencies and levels.

- Beyond central government agencies, there are a wide range of organisations and stakeholders with important national security roles and responsibilities, including local government, the private sector (eg, lifeline utilities and infrastructure operators), non-governmental organisations, and international bodies (eg, the Red Cross). In the international domain, New Zealand also works very closely with foreign countries (eg, in relation to military deployments and humanitarian assistance), regional organisations (eg, Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation, Association of South East Asian Nations and Secretariat of the Pacific Community), as well as other international institutions (eg, the United Nations).

- Central government has two distinct roles in respect to national security:

- Maintain confidence in normal conditions to ensure that policy settings, state institutions, the regulatory environment and the allocation of resources promote confidence in New Zealand society and sustain growth;

- Provide leadership in crisis conditions to ensure that potential, imminent or actual disturbances to the usual functioning of society and the economy; or interruptions to critical supplies or services cause minimum impact and that a return to usual societal functions is achieved swiftly.

- In New Zealand, similar governance and coordination mechanisms are used in both business-as-usual and crisis conditions. The focus is on managing the generic consequences instead of a specific hazard. This means that experience gained in managing one type of security problem can be readily applied to others, because the management usually involves the same stakeholders. This also has the advantage of keeping policy linked to the realities of operations.

Threshold for central government leadership

- The National Security System is made up of a number of components. Flexibility enables the National

Security System to respond at an appropriate level, with many events being managed by multi-agency

groups of senior officials. In contrast, when national leadership or involvement is required, the high-level

planning and strategic response is directed by the Prime Minister and senior members of Cabinet. - In general terms, government is likely to engage through the National Security System if New Zealand’s

key national security objectives are impacted by risks which could lead to, or cause, a crisis, event, or

circumstance that might adversely and systemically affect:- The security or safety of New Zealanders or people in New Zealand;

- New Zealand’s sovereignty, reputation, or critical interests abroad;

- The economy or the environment; or

- The effective functioning of the community.

- The criteria for issues to be managed at the national level tend to fall into two broad categories. These relate

either to the characteristics of the risks, or to the way in which they need to be managed.

Risk Characteristics

- Within the overall context set out above, the National Security System takes a particular interest in risks

that have:- Unusual features of scale, nature, intensity, or possible consequences;

- Challenges for sovereignty, or nation-wide law and order;

- Multiple or interrelated problems, which when taken together, constitute a national or systemic risk;

- A high degree of uncertainty or complexity such that only central government has the capability to tackle them;

- Interdependent issues with the potential for cascade effects or escalation.

Management requirements

- A National Security System response may be initiated for the management of risks, where any of the

following conditions apply:- Response requirements are unusually demanding of resources;

- There is ambiguity over who has the lead in managing a risk, or there are conflicting views on solutions;

- The initial response is inappropriate or insufficient from a national perspective;

- There are cross-agency implications;

- There is an opportunity for government to contribute to conditions that will enhance overall national security.

Example of a scenario when the National Security System was activated:

Operation Concord. On 27 November 2014, the Chief Executives of Fonterra and Federated Farmers received anonymous letters from someone threatening to release New Zealand infant formula, and other formula, contaminated with traces of 1080 poison, into the market unless use of 1080 in New Zealand stopped. The letters were accompanied by a plastic bag that contained a sample of infant formula contaminated with 1080.

Irrespective of whether or not the threat was carried out, it was considered to have the potential for significantly adverse consequences on consumer health, the economy and New Zealand’s international reputation. The National Security System was immediately activated.

The Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) became the lead government agency with Police leading the criminal investigation. MPI led a comprehensive, cross-government and industry response to the threat. MPI, other government agencies, dairy manufacturers and retailers, implemented comprehensive safety and vigilance measures to ensure the safety of consumers in New Zealand and overseas. The response included leadership by the Chief Executive DPMC and the Prime Minister.

For the first few months extensive use was made of senior officials’ Watch Groups (which met weekly) and the Chief Executive’s ODESC (which met fortnightly).

A public announcement regarding the threat was made on 10 March 2015. The initial media conference was jointly fronted by the New Zealand Police, the Ministry for Primary Industries and the Ministry of Health. The Prime Minister, accompanied by the Ministers for Primary Industries and Food Safety, spoke to the media later the same afternoon. New Zealand Police arrested and charged an individual in October 2015.

Following the conclusion of the National Security System activation, an independent case study was commissioned to consider the effectiveness of the response and identify important lessons. This case study underlined the value of the National Security System in the response, and identified the following key considerations in managing a crisis:

- Close coordination and collaboration of agencies;

- Strategic awareness and appreciation of national interest;

- Maintaining political, public and media confidence in the response;

- Involving non-government stakeholders;

- Communicating risk.

Part 2: National Security governance structures

- New Zealand’s arrangements for dealing with national security issues have evolved from what was for a long time known as the Domestic and External Security Coordination (DESC) system, and is now more generally referred to as the “National Security System”.

- The existence of a structured approach to national security through the National Security System does not override the statutory powers and responsibilities of Ministers or departments. Responsibility for actions and policies remains with the Chief Executive of an agency, statutory officers4 and the relevant Minister. The aim of approaching national security considerations through the construct of the National Security System is to ensure more effective coordination when agencies work together on complex problems in order to achieve better outcomes.

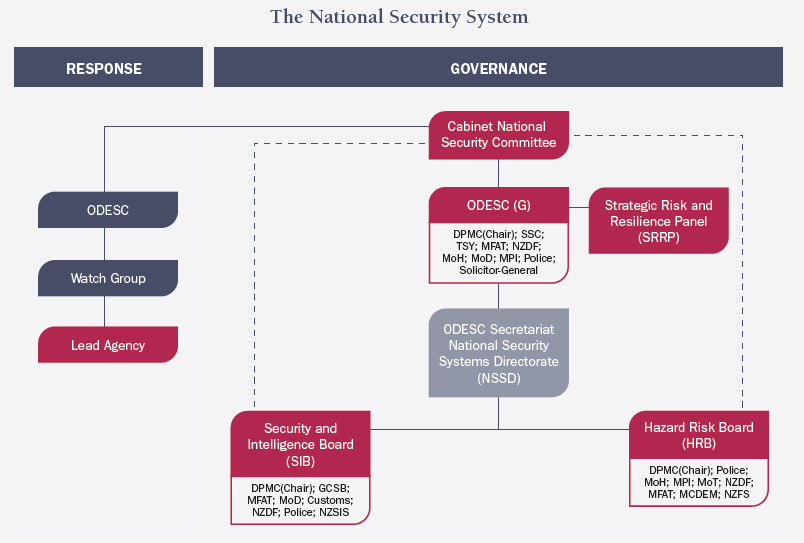

- The National Security System operates at three levels:

- Ministers (Cabinet National Security Committee), led by the Prime Minister – who also holds the portfolio of “National Security and Intelligence”;

- Chief Executives – the various structures which comprise the Officials’ Committee for Domestic and External Security Coordination (ODESC), led by the Chief Executive of DPMC – who is the “lead official” for the whole National Security System, a role encompassed by the descriptor “Chair of ODESC”;

- Senior officials and other officials (Committees, Working Groups and Watch Groups), who work together in formal structures and less formally in pursuit of shared national security objectives.

4 For example, the CDEM National Controller, Director of Public Health, Commissioner ofPolice.

Figure 2: The National SecuritySystem

Cabinet National Security Committee (NSC)

- The Cabinet National Security Committee (NSC) is a formally constituted Cabinet committee. It has oversight of the national intelligence and security sector, including policy and legislative proposals relating to the sector. The NSC coordinates and directs national responses to major crises or circumstances affecting national security (either domestic or international).

- The NSC will have Power to Act, without further reference to the full Cabinet, where the need for urgent action and/or operational or security considerations require it.

- The NSC is chaired by the Prime Minister and includes senior Ministers with relevant portfolio responsibilities: Finance, Defence, Economic Development, Communications, Attorney-General/the intelligence agencies, Foreign Affairs, Police and Immigration – with the addition of other relevant portfolio Ministers as appropriate.5

5 For details on the establishment, terms of reference and membership of the NSC see CO (14) 8.

Boards:

Officials’ Committee for Domestic and External Security Coordination (Governance) (ODESC(G))

- ODESC(G) is the primary governance board overseeing New Zealand’s national security and resilience. Its main role is the identification and governance of national security risk. ODESC(G) ensures capability and systems are in place to identify major risks facing New Zealand, and provides that appropriate arrangements are made across government to efficiently and effectively mitigate and manage those risks.

- ODESC(G) is chaired by the Chief Executive of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. ODESC(G) membership includes the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, the State Services Commission, the Treasury, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the New Zealand Defence Force, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Defence, the Ministry for Primary Industries, New Zealand Police and Crown Law. Other Chief Executives or officials may be invited by the Chair to attend ODESC(G) meetings if required.

Examples of items recently considered by ODESC(G):

- Identification and governance of strategic national risk;

- Development and maintenance of a national risk register;

- Oversight of the activities of the Hazard Risk Board and the Security and Intelligence Board.

- Note that the group of Chief Executives that meets during a crisis is known simply as ODESC (no ‘G’). ODESC will be discussed further in Part 3: The National Security System in a response.

Security and Intelligence Board (SIB)

- The purpose of the Security and Intelligence Board (SIB) is to build a high performing, cohesive and effective security and intelligence sector through appropriate governance, alignment and prioritisation of investment, policy and activity. It focuses on external threats and intelligence issues.

- SIB is chaired by the Deputy Chief Executive Security and Intelligence of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. SIB membership includes the Chief Executives of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, the Government Communications Security Bureau, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the Ministry of Defence, New Zealand Customs, New Zealand Defence Force, New Zealand Police, and the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service. Other Chief Executives or officials may be invited by the Chair to attend SIB meetings if required.

Examples of items recently considered by SIB:

- National Security workforce;

- Implementing New Zealand’s intelligence priorities;

- New Zealand’s overseas peacekeeping commitments;

- The findings of the Independent Review of Intelligence and Security 2015;

- Counter-terrorism.

Hazard Risk Board(HRB)

- The purpose of the Hazard Risk Board (HRB)6 is to build a high performing and resilient National Security System able to manage civil contingencies and hazard risks through appropriate governance, alignment, and prioritisation of investment, policy and activity.

- The HRB is chaired by the Deputy Chief Executive Security and Intelligence of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. HRB membership includes Chief Executives (or their alternates) of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, New Zealand Police, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry for Primary Industries, the Ministry of Transport, New Zealand Defence Force, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, New Zealand Fire Service and the Ministry of Civil Defence & Emergency Management.

Examples of items recently considered by HRB:

- Managing major transport risks and clarifying national arrangements for managing a major transport incident;

- Search and rescue capabilities, limitations, readiness and risks;

- Security risks of highly hazardous substances;

- Enabling effective oversight of the National Security System capability, including professional development and exercising;

- Improvements to the system following lessons identified during Operation Concord (1080 threat).

6 The Hazard Risk Board (HRB) was previously called the Readiness and Response Board (RRB). Its name changed in 2015.

Strategic Risk and Resilience Panel (SRRP)

- The purpose of the SRRP is to provide a rigorous and systematic approach to anticipating and mitigating strategic national security risks. It promotes resilience by testing, challenging and providing advice to ODESC(G). The SRRP, which functions as “a critical friend of ODESC(G),” is an independent panel. It will respond to specific tasks or requests for advice from the Chair of ODESC(G) and will provide recommendations accordingly, but it sets its own work programme, agenda and meeting rhythms. Secretariat services are provided by DPMC (NSS Directorate).

- Members are appointed by the Chair of ODESC(G), and are selected according to their expertise, rather than as a representative of any specific agency or organisation. The SRRP consists of 7-10 members, mostly from outside government.

Secretariat for the ODESC governanceboards

- DPMC (NSS Directorate) provides the secretariat for all the ODESC governance boards, including the Strategic Risk and Resilience Panel. Further information including Terms of Reference for each board, can be provided on request by DPMC (NSS Directorate).

Working Groups and committees

- The boards are supported by a number of multi-agency Watch Groups, Working Groups and committees; details of these can be provided by DPMC (NSS Directorate). Committees are typically longstanding while working groups are usually formed as required to concentrate on a specific issue. Watch Groups are formed in response to a potential, emerging or actual event; more details are in Part 3: The National Security System in a response.

- Membership of committees and Working Groups depend on the nature of the issue under consideration. Attendees should be senior and experienced enough to add value to the deliberations of the group, contribute to its decision making and, on occasion, make commitments or confirm decisions on behalf of their agency.

Committee examples

- Reporting toSIB:

- Counter-Terrorism Coordinating Committee(CTCC);

- National Intelligence Coordination Committee(NICC);

- Mass Arrivals Prevention Strategy Steering Group(MAPS);

- Major Events Security Committee(MESC).

- Reporting toHRB:

- Maritime Security Oversight Committee(MSOC);

- National Exercise Programme(NEP);

- National Agencies' Incident Management Reference Group(IMRG);

- New Zealand Search and RescueCouncil.

How do ODESC(G), SIB and HRB operate?

Each board has a meeting schedule, with a forward agenda typically mapped out for the coming year (ie, the topics for discussion are scheduled in advance). Invariably, additional items arise and are added to the agenda. If required, supplementary meetings can be scheduled and, in some circumstances, out-of-session papers can be circulated.

Each item on the agenda consists of a paper and a coversheet. These, along with the agenda, are consolidated at least six working days prior to the meeting and circulated at least five working days in advance. Successful meetings occur when those attending have a good understanding of the issue at hand, including the implications for their own agency. Officials normally assist their attendee (“principal”) by briefing them prior to the meeting. It is therefore important for all agencies to get their papers in to DPMC (NSS Directorate) on time, so that Chief Executives receive them in a timely manner.

Preparing a paper

It is wise to discuss proposed papers with the Secretariat (DPMC NSS Directorate) as early as possible. DPMC (NSS Directorate) is able to provide advice regarding the timing of a given paper, and whether the Chair is likely to accept the item onto the agenda. Senior officials’ groups associated with each board assist in confirming agendas and ensuring that papers are ready.

Where possible, papers should be circulated to agency officials during the preparation stage so that differing views can be incorporated. It may be beneficial to formally consult agencies during this period (eg, request a response from Chief Executives), and note this in the paper. There have been situations where officials have not appreciated their own Chief Executive’s view or that of a significant stakeholder prior to finalising a paper. This is obviously awkward, and results in an item not being progressed when it could have been.

Guidance on writing a formal paper including how to form recommendations can be found in the Cabinet Guide (the Policy Paper template) available from www.dpmc.govt.nz

Lead agency

- For any national security risk (or major element of such a risk), a lead agency is identified. The lead agency is the agency with the primary mandate for managing a particular hazard or risk across the “4Rs” of risk reduction, readiness, response and recovery. Whilst some risks are managed by the lead agency alone, many require the support of other government departments and agencies.

- National security challenges are often complex and cut across a range of agencies and sectors. When there is ambiguity as to who should be the lead, agencies are expected to consult with the Chief Executive of DPMC at the earliest opportunity in order to resolve doubt and confirm arrangements.

- The principal reasons for having nominated lead agencies, and setting clear expectations of them, are as follows:

- To ensure clarity and certainty about responsibilities and leadership at a time of crisis;

- To ensure responsibilities for horizon scanning and risk mitigation are assigned properly;

- To give early warning and more time for decision-making;

- To facilitate prompt response, thereby avoiding compounding damage;

- To give clarity on communications lines and the provision of necessary information;

- To ensure structures and coordination, including contingency planning, are in place before crises occur;

- To have designated responsibilities for both proactive and reactive risk management.

- Where activities are required at national, regional or local levels, a devolved accountability model is used. For example, the Ministry of Health is the strategic lead for infectious human disease nationally, while District Health Boards are the regional lead. Maritime New Zealand is the national lead for a marine oil spill, with the regional lead being the responsibility of the affected Regional Council.

- The responsibilities of a lead agency with specific regard to emergencies are set out in clause 14 of the National CDEM Plan Order 2015. These include:

- A lead agency is the agency with the primary mandate for managing the response to an emergency, and at the

national level the lead agency’s role is to—

(a) monitor and assess the situation; and

(b) plan for and coordinate the national response; and

(c) report to the ODESC and provide policy advice; and

(d) coordinate the dissemination of public information. - A lead agency—

(a) should develop and maintain capability and capacity to ensure that it is able to perform its role; and

(b) may draw on the advice and expertise of expert emergency managers in doing so.

- A lead agency is the agency with the primary mandate for managing the response to an emergency, and at the

- Although it does not reference them specifically, these responsibilities are equally applicable to those agencies who have a lead on traditional security threats. A list of lead agencies for a number of national hazards and security threats is listed in Table 1.

Support agencies

- Agencies supporting the lead agency are known as support agencies and are required to develop andmaintain capability and capacity to ensure that they are able to perform their role7. It should be notedthat support agencies may have statutory responsibilities and/or specific objectives of their own, whichthey may need to pursue in addition to, or as part of, the support that they provide to the lead agency.Sometimes, a support agency might support the lead agency simply by repurposing an existingcapability.

7Section 15(1) National CDEM Plan Order2015

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’srole

- The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (DPMC)’s mandated role is to:

- Scan for domestic and external risks;

- Assess domestic and external risks of national security significance;

- Coordinate policy advice and policy making to ensure that risks are managed appropriately;

- Coordinate government action to deal with national security risks. This can include coordinating across lead agencies when multiple events are occurring at the same time.

- As described earlier, DPMC chairs and provides the secretariat for the governance boards. These include ODESC(G), SRRP, SIB, HRB and ODESC. DPMC also usually chairs and supports Watch Groups though in some circumstances the Watch Group chair and support functions might be carried out by the lead agency instead. This would be a matter for discussion and mutual agreement between DPMC and the agency concerned.

- The Chief Executive of DPMC is New Zealand’s lead official for national security, and heads the national security architecture. The Deputy Chief Executive Security and Intelligence of DPMC supports the Chief Executive by leading and coordinating the national security system in its practical application. He oversees the functioning of the system, advises on national security direction and ensures that policies, systems and capabilities are up to standard. He has a specific role leading and coordinating the New Zealand Intelligence Community.

- The Director of National Security Systems of DPMC ensures that the system architecture performs as intended; implements the decisions of the ODESC system; builds specific capabilities; remains alert to current events requiring a national security response; activates the system when necessary; and ensures that experience is retained as knowledge within the system.

Table 1: Lead agencies

These agencies are mandated (either explicitly throughlegislationor because of their specific expertise) to manage anemergencyarising from the following hazards8.

|

HAZARD |

LEAD AGENCYATNATIONALLEVEL |

LEAD AGENCY AT LOCAL/REGIONALLEVEL |

AUTHORITY TOMANAGE RESPONSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geological (earthquakes, volcanic hazards, landslides, tsunamis) | Ministry of Civil Defence & Emergency Management | Civil Defence Emergency Management Group | CivilDefenceEmergencyManagement Act2002 |

| Meteorological (coastalhazards, coastal erosion, storm surges, large swells, floods, severe winds, snow) |

Ministry of Civil Defence & Emergency Management |

Civil Defence Emergency Management Group |

CivilDefenceEmergencyManagement Act2002 |

| Infrastructure failure | Ministry of Civil Defence & Emergency Management | Civil Defence Emergency Management Group | CivilDefenceEmergencyManagement Act2002 |

| Drought (affecting rural sector) | Ministry for Primary Industries | Ministry for Primary Industries | Government policy |

|

Animal and plant pests and diseases (biosecurity) |

Ministry for Primary Industries |

Ministry for Primary Industries |

Biosecurity Act 1993 Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996 |

| Food safety | Ministry for Primary Industries | Ministry for Primary Industries | Food Act 2014 |

|

Infectious human disease (pandemic) |

Ministry of Health |

District Health Board |

Epidemic Preparedness Act 2006 Health Act 1956 |

| Offshore humanitarian response | Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade | Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade | Agency mandate and offshore network/expertise |

| Wild fire | New Zealand Fire Service |

Rural Fire Authority Department of Conservation (Conservation estate) New Zealand Defence Force |

Forest and Rural Fires Act 1977 Conservation Act 1987 Defence Act 1990 |

| Urban fire | New Zealand Fire Service | New Zealand Fire Service | Fire Service Act 1975 |

|

Hazardous substance incidents |

New Zealand Fire Service |

New Zealand Fire Service |

Fire Service Act 1975 Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996 |

| Major transport accident | Ministry of Transport9,10 | New Zealand Police | Various |

| Marine oil spill | Maritime New Zealand | Regional council | Maritime Transport Act 1994 |

|

Radiation incident |

Ministry ofHealth |

New Zealand Fire Service |

Radiation Protection Act 1965 Fire Service Act 1975 |

|

Terrorism |

New Zealand Police |

New Zealand Police |

Crimes Act 1961 International Terrorism (Emergency Powers) Act 1987 Terrorism Suppression Act 2002 |

|

Espionage |

New Zealand Security Intelligence Service |

New Zealand Security Intelligence Service |

New Zealand Security Intelligence Service Act 1969 Government policy |

|

Major cyber incident |

Government Communications Security Bureau - operational lead Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (National Cyber Policy Office) - policy lead |

Government Communications Security Bureau - operational lead Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (National Cyber Policy Office) - policy lead |

Government Communications Security Bureau Act 2003 Government policy |

8 This table is largely, although not wholly, based on Appendix 1, National CDEM Plan Order 2015

9 The lead Minister will be the Minister of Transport supported by their Ministry and the respective legislation

10 New Zealand Police are listed in the Plan as the operational lead

Part 3: New Zealand's National Security System in response to a potential, emerging or actual event

Activation criteria

- Crises or events that impact New Zealand or its interests can occur at any time, and at a variety of scales. The National Security System is activated11 when one or more of the following apply:

- Increasing risk, or a disaster or crisis, affects New Zealand interests;

- Active, or close coordination, or extensive resources are required;

- The crisis might involve risk to New Zealand’s international reputation;

- An issue is of large scale, high intensity or great complexity;

- Multiple smaller, simultaneous, events require coordination;

- An emerging issue might meet the above criteria in the future, and would benefit from proactive management.

Examples of National Security System activations:

- Threat of 1080 contamination of infant formula;

- Ebola viral disease readiness and possible Ebola case;

- Neurological complications and birth defects possibly associated with Zika virus;

- Threat of a domestic terrorist incident;

- TS Rena grounding on Astrolabe Reef 2011;

- Darfield Earthquake 2010 and Christchurch Earthquake 2011.

The National Security System can be activated for more than one issue at any one time.

11 The Annexes include the section “What does a National Security System activation involve?”

- The National Security System provides for a coordinated government response in which:

- Risks are identified and managed;

- The response is timely and appropriate;

- National resources are applied effectively;

- Adverse outcomes are minimised;

- Multiple objectives are dealt with together;

- Agencies’ activities are coordinated.

- As every event is different, the National Security System response needs to be flexible. In many cases, the event is sufficiently coordinated at the Watch Group (senior official) level, without any other components being involved.

Government objectives

- As described in Part 1, the government has seven overall national security objectives. In responding to a national security crisis, government’s specific objectives will be to:

- Ensure public safety, protect human life and alleviate suffering;

- Preserve sovereignty, and minimise impacts on society, the economy, and the environment;

- Support the continuity of everyday activity, and the early restoration of disrupted services; and

- Uphold the rule of law, democratic institutions and national values.

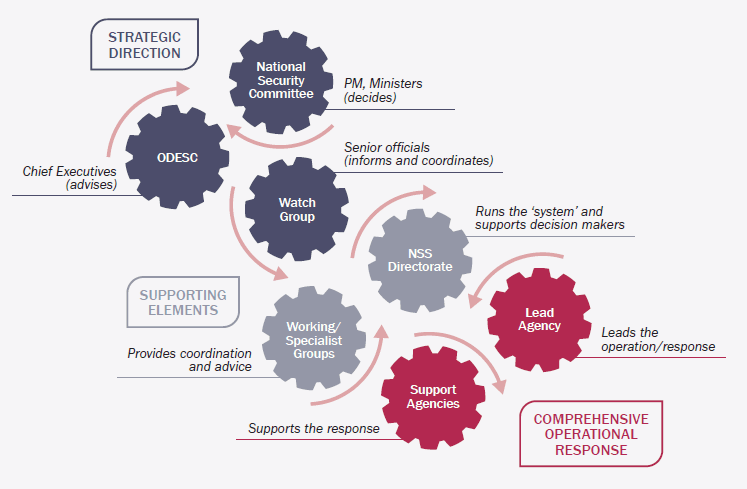

Crisis governance structure

- As with business-as-usual activity, the National Security System operates at three levels during a crisis response:

- • Ministers (Cabinet National Security Committee), led by the Prime Minister;

- • Chief Executives (ODESC), led by the Chief Executive of DPMC12;

- • Officials (Watch and Specialist Groups), led by the Deputy Chief Executive; Security and Intelligence, DPMC.13

12 Alternate is the Deputy Chief Executive Security and Intelligence, DPMC

13 Alternate is the Director of National Security Systems, DPMC

Intersection of ODESC with CIMS

- New Zealand’s “Coordinated Incident Management System” (CIMS) is a framework of consistent principles, structures, functions, processes and terminology that agencies can apply in an emergency response. It enables agencies to plan for, train and conduct responses in a consistent manner, without being prescriptive. CIMS relates to the management of a response; the ODESC structure sits above this if the situation is significant or complex enough to demand a coordinated strategic response at the national level. The lead agency under the CIMS framework would also be the lead agency with respect to the ODESC response. The “Controller” (a formal CIMS designation) should expect to have a role briefing Watch Group and ODESC meetings. DPMC (NSS Directorate) will also appoint a liaison officer to manage the interface between the operational response (CIMS) and the strategic response (ODESC).

National Security System in a crisis

Figure 3: National Security System in a crisis

Escalate early

- National security issues often move at speed. Effects spread quickly, and the ‘ask’ on the lead agency can accumulate swiftly. There is therefore a bias towards activating the National Security System early. This ensures that suitable mechanisms are in place if or when they are needed, even if they subsequently turn out not to be needed after all.

Officials Committee for Domestic and External Security Coordination (ODESC)

- “ODESC” is the overall phrase to describe the formal structure of senior officials which manages national security in New Zealand in both its governance (described earlier) and its response modes (described here).

- ODESC is also the name for the committee of Chief Executives which, during an emerging or actual security event, is responsible for providing strategic direction and coordinating the all-of-government response. ODESC is chaired by the Chief Executive of DPMC who will invite Chief Executives to attend as required. In his absence, ODESC will be chaired by the Deputy Chief Executive Security and Intelligence, DPMC.

- ODESC:

- Provides all-of-government coordination at the Chief Executive level of the issues being dealt with through the response;

- Provides strategic advice on priorities and mitigation of risks beyond the lead agency’s control;

- Ensures that the lead agency and those in support have the resources and capabilities required to bring the response to an effective resolution;

- Provides the linkages to the political level, including supporting Ministers to make decisions about strategic policy, authorisation of resources or any other decisions which sit within Ministers’ ambit of control;

- Exercises policy oversight and advises the Prime Minister, Cabinet, and, when activated, the Cabinet National Security Committee, accordingly

- ODESC takes advice from the Watch Group, the lead agency and the ODESC members around the table. Members apply their collective judgment and experience in assessing the high-level strategic implications of the issue and agreeing on response options.

- Usual conventions about the roles and responsibilities of Ministers, Chief Executives and senior officials with respect to decision-making continue to apply. These are set out in the Cabinet Manual and in various pieces of legislation. These should be well understood by ODESC attendees, given the speed at which decisions may be required during a response.

ODESC membership

- When ODESC meets to deal with a crisis or developing event, the membership reflects the situation. The Chief Executive of DPMC is always the Chair of ODESC (or, in his/her absence, the Deputy Chief Executive Security and Intelligence). The Chief Executive of DPMC will invite colleagues to attend an ODESC meeting as s/he deems necessary, having regard to the issues in play. ODESC should be attended by Chief Executives. Substitutes are only permitted in exceptional circumstances, with the prior agreement of the Chair.

- Only invitees are permitted access into the ODESC meeting room. Agency policy advisors or support staff must to be kept to a minimum and will only be invited into the ODESC meeting room with the agreement of the Chair, if absolutely required (eg, if required to brief the meeting).

Examples of ODESC meetings recently held to consider potential, emerging or actual events

- Implications for New Zealand of the terrorist attacks in Paris (2015);

- Security arrangements for the Cricket World Cup (2014-2015);

- Ebola Viral Disease outbreak (2014);

- Operation Concord (1080 contamination threat) (2014-2015).

Watch Groups

- A Watch Group may be called by DPMC to monitor a potential, developing or actual crisis. Frequently Watch Groups alone are enough to achieve cross-agency coordination, and the other levels (ODESC or NSC) are not required.

How do Watch Groups ‘kick off’?

A Watch Group will be called by DPMC’s National Security System Directorate (NSS Directorate) if it becomes aware of a potential, emerging or actual issue that:

- Affects New Zealand’s interests or international reputation;

- Requires active or close coordination, or extensive resources;

- Is of large scale, high intensity or great complexity;

- Requires coordination of multiple, smaller, simultaneous events; or

- Might meet one of these conditions in the future and would benefit from swift attention before things deteriorate.

DPMC’s NSS Directorate finds out about such issues through being told by an agency (eg, 1080 contamination threat), hearing about it in the media (eg, Paris terrorist attacks), or from other information flows (eg, terrorist issues within New Zealand).

DPMC’s NSS Directorate runs a 24/7 duty officer roster to ensure that issues can be triaged and evaluated swiftly, even if they arise out of hours. If you’re concerned about an issue but are not sure whether it meets the threshold for activation, talk to DPMC’s NSS Directorate.

Once aware of an issue, DPMC’s NSS Directorate consults internally, including with the Deputy Chief Executive Security and Intelligence and, if significant enough, with the Chair of ODESC. Discussion will also be held with the NSS Directorate agency. Such discussions determine whether it would be useful to call a Watch Group.

Agencies will be informed about the Watch Group via email and, if necessary, phone call. As much notice as possible is given, but for fast moving events this can be minimal.

- Watch Groups are a tool to obtain situational clarity in what is often a chaotic environment, and are responsible for ensuring that systems are in place to ensure effective management of complex issues. The Chair of the Watch Group reports on the Watch Group’s assessments and advice to ODESC.

- Watch Groups focus on the national interest and remain at a strategic level. Watch Group members test current arrangements, check with each other to ensure that all risks have been identified and are being managed, identify gaps and areas of outstanding concern, and agree on any further action required.

- A role card for staff attending Watch Groups is included in the Annexes.

Chair’s key considerations – an Aide Memoire

In preparing for a Watch Group, the Chair will consider the following aspects of the event (this is not an exhaustive list):

- The health and wellbeing of New Zealanders and people in New Zealand;

- Economic impacts on New Zealand;

- New Zealand’s foreign relationships;

- Expectations of a responsible government (ie, are we doing all that a reasonable person would expect us to be doing);

- Public information.

- Particularly during a fast moving event, Watch Groups will make some decisions in their own right. Such decisions are usually operational and relate to taking one or another course of action. In general, decisions that are irreversible and commit New Zealand to a certain course of action will be taken by ODESC or the Cabinet National Security Committee, depending on the scale and significance of the decision.

Output

- Accurate recordkeeping of the deliberations and decisions of Watch Groups and ODESCs is extremely

important. This task falls to DPMC (NSS Directorate) unless prior agreement has been made with the

lead agency. - The products of Watch Groups might include:

- A record of the meeting, including action items and decisions (always);

- A brief to ODESC (or, at a minimum, a brief to the Chair of ODESC) (usually);

- A briefing note to Ministers (if needed);

- Media talking points (depending on circumstances);

- Intelligence requirements (depending on circumstances).

Composition and chair

- Watch Groups are ordinarily made up of senior officials able to commit resources and agree actions on behalf of their organisation. The exact composition of Watch Groups depends on the nature of the event, and includes agencies with a role to play in responding to the issue at hand. Sometimes this might include agencies which do not usually think of themselves as “national security” agencies and do not have a lot of experience in operating within the National Security System structures. The role cards and other information in this handbook are intended to assist agencies in this circumstance. DPMC (NSS Directorate) can also provide additional assistance, advice and coaching.

- Each agency typically sends one representative although the lead agency may also have representatives from the operational response (ie, the Controller, communications and legal professions). Alternatively, these disciplines may be represented by members of their respective working groups.

- The Deputy Chief Executive Security and Intelligence, DPMC, has the formal role of Watch Group Chair. In practice, this may be delegated to the Director National Security Systems (NSS), DPMC or, by prior agreement, to the lead agency. DPMC (NSS Directorate) will set the time and agenda for the meetings, in discussion with the lead agency. DPMC’s Policy Advisory Group may have a representative in attendance, depending on the issue. (The Policy Advisory Group has a specific function with respect to supporting the Prime Minister which is separate from, although complementary to, DPMC’s national security structure.)

Zika Watch Group

In early February 2016, after the World Health Organisation declared the neurological complications and birth defects possibly associated with Zika to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, a Watch Group was held to discuss Zika in relation to New Zealand.

Agencies involved at the first meeting included:

- Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (National Security Systems, National Security Policy, National Security Communications, National Assessments Bureau, Policy Advisory Group);

- Ministry of Health (Chief Medical Officer, Director and Deputy-Director of Public Health, Communicable Diseases, Environmental and Border Health, Emergency Management);

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (International Development Group, Consular Services, HR);

- Ministry for Primary Industries;

- Ministry for Pacific Peoples;

- New Zealand Customs Service;

- New Zealand Police;

- New Zealand Defence Force.

The agenda canvassed:

- Situation update: what do we know?

- Activity: what are we doing?

- Communications (with public and Ministers)

- What else should or could we be doing?

- Any other issues or risks?

Frequency and scheduling

- The nature of the crisis will determine how often the Watch Group meets. In the initial period after a no-notice event, Watch Groups may meet twice daily. For emerging events, Watch Groups may meet weekly or monthly. It is common for Watch Groups to meet more frequently than ODESC. ODESC meetings are normally preceded by a Watch Group, which will consider the issue and prepare advice to ensure that Chief Executives’ deliberations can be as effective as possible.

Watch Group examples

Watch Groups typically meet prior to each ODESC meeting – although there may not be an ODESC meeting just because a Watch Group has been called.

Examples of when Watch Groups have met without a follow-up ODESC include:

- Tongariro volcanic eruption in 2012

- Kidnapping of a New Zealand citizen in Nigeria

- Zika virus

- Security arrangements for ANZAC commemorative events in Gallipoli.

Across the National Security System, a Watch Group is typically held on one or another topic every one to two weeks.

Working Groups and Specialist Groups

- Working or Specialist Groups form when it is desirable for a profession or discipline to determine and present a consolidated view, or specific advice, to a Watch Group or ODESC. If this consolidated view is not provided, Watch Group and ODESC meetings might be dragged into the detail and get diverted into carrying out the analysis themselves without necessarily having the right background to do this effectively.

- Working Groups and Specialist Groups are normally activated by the lead agency or by DPMC (NSS Directorate).

- Whilst an ad-hoc Working Group can be formed for a specific crisis, there are a number of specific ones.

Government LegalNetwork

- The Government Legal Network (GLN) ensures that relevant legal issues are identified and managed in

a coordinated manner. GLN members are expected to:- Quickly come together to identify legal risks associated with fast moving scenarios;

- Be prepared to develop and provide joined up legal advice to National Security System meetings.

This advice should be:- Concise;

- Solution oriented;

- Comprehensive (conflicts are, where possible, worked through and resolved);

- Focused on supporting the delivery of operational outcomes (the response should not become driven by legal considerations).

- To ensure that legal risks are managed appropriately and the legal effort operates in support of operational objectives it is likely that a representative from the GLN will be asked to attend Watch Group and possibly also ODESC meetings. Typically this representative will come from either the lead agency or from Crown Law. This representative will be expected to be able to speak authoritatively on behalf of the GLN. The Watch Group and ODESC Chairs will rely on the legal advice provided by the GLN in determining the

appropriateness of the planned response. - Agency lawyers are aware of how to activate the GLN.

Policy Coordination Group

- The Policy Coordination Group coordinates policy development, if required, during a crisis. It is chaired by DPMC’s National Security Policy Directorate and is attended by policy leads from the lead agency and other relevant agencies.

- It is important that policy units are involved early on in a crisis. They may be called upon to provide advice on current policy positions, develop crisis-specific policy advice or be required to develop significant policy options (including legislative review) following the event. Full and properly coordinated engagement will ensure that Ministers and ODESC receive the best policy advice – free, frank and full – during and after the crisis.

Economic Advisory Group

- The purpose of the Economic Advisory Group (EAG) is to coordinate economic and financial market advice to ODESC in the event of a major national emergency event. The EAG is chaired by Treasury, with the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment and the Financial Markets Authority forming the core membership. Depending on the specific event, other agencies (most likely Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Ministry for Primary Industries and Ministry for the Environment) may also be invited to attend.

AoG Strategic Communications

- The AoG Strategic Communications function assists the lead agency by managing the strategic communications related to the event, leaving the lead agency to focus on operational communications requirements.

- Strategic communications officials contribute to ODESC meetings, brief Ministers on strategic communications plans, and coordinate messaging with the lead agency’s Public Information Management (PIM)14 Manager.

- A focus is on ensuring stakeholders are supported, messages are appropriate, and the lead agency has sufficient staff to manage media and public information requirements.

- The AoG Strategic Communications function is led by DPMC’s Director, National Security Communications, or by arrangement with the lead agency or other agencies involved in the response.

Science Network

- The Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor may have a role in ensuring that ODESC receives effective and coordinated advice on the scientific aspects of the event. Lead agencies may also establish Technical Advisory Groups (TAG), Scientific Advisory Groups (SAG) or Scientific Technical Advisory Committees (STAC). These will usually provide advice to the lead agency or agencies, rather than direct to the Watch Group or ODESC.

14 Public Information Management is a function under the Coordinated Incident Management System(CIMS).

Intelligence Community

- A number of components form the New Zealand intelligence community. These include:

- National Assessments Bureau (NAB). NAB is the leader of New Zealand’s intelligence assessments community and provides overall coordination of New Zealand’s intelligence collection efforts through its leadership of the national intelligence priorities. NAB provides assessments to assist decision-makers on events and developments relevant to New Zealand’s national security and international relations. NAB is a unit of DPMC.

When the National Security System is activated, the NAB’s focus is to ensure that a consolidated, assessed intelligence picture is delivered at meetings and that there is a coordinated intelligence collection plan. This is achieved by bringing the intelligence agencies together before meetings to ensure a coherent picture is delivered. NAB uses its position in the intelligence community to drive a speedy and coordinated response to any intelligence questions raised by the Watch Group, ODESC or the Cabinet National Security Committee. - New Zealand Security Intelligence Service (NZSIS). NZSIS’ primary role is to investigate threats to security. It works with other agencies within government, so that the intelligence it collects is actioned, and threats which have been identified are disrupted. It also collects foreign intelligence, and provides a range of protective security advice and services to government.

- Combined Threat Assessment Group (CTAG). CTAG informs government’s risk management processes by providing timely and accurate assessment of terrorist threats to New Zealanders and New Zealand’s interests. When the National Security System is activated in response to a domestic terrorist issue, CTAG will be expected to provide the assessment for the Watch Group. CTAG is a unit of NZSIS.

- Government Communications Security Bureau (GCSB). GCSB provides foreign intelligence to the New Zealand government. It also has a role in the provision of information assurance and cyber security to government and other critical organisations.

- New Zealand SIGINT Operations Centre (NZSOC). NZSOC provides a 24/7 threat warning service based on the combined efforts of the Five-Eyes watch-keeping services. These bring together and fuse information from a variety of sources in order to alert the New Zealand government to incidents and threats around the world in a timely manner. NZSOC is a unit of GCSB. NZSOC is able to contact the DPMC (NSS Directorate) duty officer at any time, day or night.

- Other agencies. A number of other government agencies, including NZDF, Police, Immigration NZ, Customs and MPI also have intelligence teams. These will work together in the production of coordinated intelligence products, where relevant, to contribute to the issue in question.

- National Assessments Bureau (NAB). NAB is the leader of New Zealand’s intelligence assessments community and provides overall coordination of New Zealand’s intelligence collection efforts through its leadership of the national intelligence priorities. NAB provides assessments to assist decision-makers on events and developments relevant to New Zealand’s national security and international relations. NAB is a unit of DPMC.

Border Agencies

- A number of agencies make up the Border cluster. Which specific agencies are asked to participate in an event will depend on the nature of the event. Agencies include New Zealand Customs Service, Immigration New Zealand (Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment), the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the Ministry for Primary Industries, the Ministry of Health, Maritime New Zealand, Aviation Security Service, Civil Aviation Authority, New Zealand Defence Force, New Zealand Police and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

Senior Officials’ Group and Governance Groups

Some events (such as regional flooding), do not meet the criteria for activation of the whole National Security System, but the lead agency might decide to use a Senior Officials’ Group for similar purposes to a Watch Group, at an operational rather than a national/strategic level.

Other agencies may request senior officials to attend a response Governance Group; see the CIMS guideline for more information.

Emergency Task Force

An Emergency Task Force (ETF) is a Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade-led group that is established in the lead up to, or following, an off-shore event that may result in New Zealand providing humanitarian assistance. The ETF collectively considers possible options and, in consultation with relevant members, plans and coordinates an appropriate response. Agencies participating in the ETF include the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Chair), the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, the Ministry of Civil Defence & Emergency Management, the Ministry of Health, New Zealand Defence Force, New Zealand Fire Service, New Zealand Police and, if appropriate, representatives from the French Embassy and Australian High Commission. In addition, a number of non-governmental organisations such as the Red Cross and Council for International Development may attend.

ETFs are frequently called during the cyclone season.

An ETF is not a Watch Group, and is not considered to be part of the formal ODESC structure.

DPMC Directorates

- A number of business units within DPMC might be involved in a national security event. Their key

roles are:

Ministry of Civil Defence & Emergency Management

- To provide policy advice to government on issues relating to civil defence and emergency management;

- To support civil defence and emergency management planning and operations;

- (In a civil defence emergency) to ensure that there is coordination at local, regional and national levels;

- To manage the central government response for large scale civil defence emergencies that are beyond the capacity of local authorities.

National Security Systems

- To provide support to the Prime Minister and Chairs of ODESC and Watch Group to enable them to take well informed and timely decisions. This can involve briefings, reports and secretariat support including good recordkeeping, as well as chairing Watch Groups;

- To coordinate the National Security System by ensuring that the right agencies are represented at meetings, understand their roles and responsibilities and follow through on action points.

National Security System (all hazards) weekly update

DPMC (NSS Directorate) manages the National Security Systems (all hazards) weekly update which provides situational awareness across government. Whilst its primary purpose is to inform ODESC members, it also enhances inter-agency situational awareness at all levels. Risks are captured in a regular and transparent manner, and early warning of potential or emerging issues, including those that collectively impact several agencies, are documented.

In addition, the weekly update builds and enhances cross-agency networks and raises awareness of system activity.

The weekly update is circulated to Hazard Risk Board Chief Executives and officials across National Security System agencies.

National Security Policy

- To provide briefing and decision support to the Chief Executive of DPMC and/or the Chairs of Watch Groups and ODESC meetings;

- To provide policy advice and support to the Prime Minister and portfolio Ministers, and lead crossagency coordination of policy advice and deliverables.

National Assessments Bureau (NAB)

- To ensure that assessments are available to assist decision-makers in making sense of the events in their broader context, including as they may be relevant to New Zealand’s national security and/or international relations;

- More information on NAB is included in the Intelligence Community section (p34).

National Security Communications

- To liaise with the media team in the Prime Minister’s Office;

- To provide public information management advice to the Chief Executive of DPMC; the Chairs of Watch Groups and ODESC; and/or Ministers;

- To ensure that the Strategic Communications aspect of the response has stood up and is working effectively.

Policy Advisory Group

- To provide direct assurance advice (second opinion) to the Prime Minister;

- To provide support to DPMC’s NSS Directorate and the Chairs of ODESC and Watch Groups on the Prime Minister’s and Ministers’ likely needs with respect to the event.

- Further information about the role of DPMC’s business units can be found at www.dpmc.govt.nz/dpmc

Lead agency responsibilities

- Generic information about the role of a lead agency was provided earlier (paragraph 41).

- The lead agency’s main responsibility in an ODESC or Watch Group meeting is to ensure that supporting agencies are provided with sufficient information about the incident and resulting actions to support ODESC or Watch Group’s consideration of strategic priorities, risks and further actions required.

- Lead agencies are normally responsible for providing an initial overview (first meeting), or update on the situation (subsequent meetings). Whilst this can be presented verbally, the use of targeted visual aids such as PowerPoint slides or maps is often beneficial.

- Normal CIMS outputs such as Situation Reports and Action Plans should be produced. In a National Security event, these need to encompass all aspects of the response.

- Situation Report (SitRep). The SitRep needs to be comprehensive enough to give supporting agencies a common picture of the incident. A suggested SitRep template is included in the Annexes. The SitRep is normally circulated regularly. It forms the basis for the situation update provided at the start of Watch Group and ODESC meetings.

- National Strategic Plan. This is a form of a high-level Action Plan that documents what is being done to address the incident, including:

- High level objectives

- Key risks

- Objectives or lines of effort

- Roles and responsibilities

- Strategic communications plan

- There are several formats of a National Strategic Plan; a suggested template is included in the Annexes.

- Aides Memoire/Ministerial Briefings. While normal lines of communication between agencies and their Ministers should continue, it is preferable that agencies draw on a single source of the truth in preparing briefing material for individual Minister(s), to avoid creating confusion or information gaps. The more significant and swifter-moving the crisis, the more important it is that agencies are joined up in delivering briefings and updates to Ministers.

- It is usually beneficial for the lead agency to circulate their Aides Memoire/Ministerial Briefings to the supporting agencies as this assists in consistent messaging to Ministers. Supporting agencies generally forward the lead agency’s Aide Memoire with a covering note, or incorporate the material into their own documentation.

Agency responsibilities (all agencies)

- Agencies should proactively consult with DPMC (NSS Directorate) regarding any actual, emerging or potential threat.

Example of a potential National Security System issue not requiring activation

In October 2015, a threat to carry out a shooting at the University of Otago was made online. Two copycat threats were made the next day. DPMC (NSS Directorate) liaised with Police and monitored the issue. Officials concluded that there was no significant, complex or imminent threat and that activation of the National Security System was not required.

http://www.odt.co.nz/news/dunedin/358373/shooting-threat-otago-university

This example illustrates that determining whether to call a Watch Group is not always clear cut and requires judgement. In this case, the assessment was made that Police had sufficient resources to manage the situation. It was believed to be a hoax (similar events were occurring overseas at the same time).

A Watch Group would have been called if the situation deteriorated, if the Commissioner of Police had asked for activation, or if Police had wanted a second opinion on the next steps.

- Once informed about a National Security System event, agencies should proactively activate support arrangements and specialist groups where needed. Agencies are expected to liaise internally with relevant business units such as communications and legal.

Importance of agency internal processes

The Exercise Rawaho 2015 evaluation stressed that agencies need to validate their internal arrangements for effective receipt and distribution of information in the activation and operational phases of a national security event. Information does not always reach the right people within agencies because of poor agency internal processes or outdated contact lists.

Processes and contact lists need to reflect that incidents can occur at any time. In early 2016 alone, the terrorist attacks in Brussels, a Christchurch aftershock and changes to arrangements in response to Tropical Cyclone Winston all occurred after-hours.

- Information gathering should commence early and agencies should proactively assess the situation. This assists in providing relevant advice and intelligence to assist decision-making by Watch Groups and ODESC within the timeframe that’s likely to be required.

- Agencies are responsible for ensuring that their representatives attending Watch Group or ODESC:

- Are senior officials able to commit resources and agree actions on behalf of their organisation;

- Are ready to provide status reports, outline their agency’s response, and contribute advice for collective decision-making. Representatives are expected to actively contribute to Watch Group or ODESC;

- Are well versed in their agency’s statutory obligations and its role in response and recovery;

- Have a good understanding of National Security System arrangements and the response plan(s) for the crisis at hand;15

- Are familiar with supporting information relating to the crisis, including that distributed during the response;

- Hold the required security clearance.

ODESC and Watch Group meetings – location and security clearance

- In most instances, meetings of Watch Groups and ODESC will be convened in Pipitea House, 1-15 Pipitea Street, Thorndon, Wellington. On occasion, the lead agency may host Watch Group meetings. ODESC may, depending on the circumstances also be held in the office of the Chief Executive of DPMC, Level 8, Executive Wing, Parliament Buildings (Beehive).

- When the National Crisis Management Centre (NCMC) is activated (eg, a terrorist incident or an emergency caused by a natural hazard), meetings of Watch Groups and ODESC will be held in the NCMC which is located in the Beehive basement.

Pipitea House

- Access into Pipitea House is strictly controlled; the names of those attending must be provided by DPMC to the reception staff in advance of the meeting. Names are normally required 24 hours in advance however exceptions can be made for a fast-moving emergency. Proof of identity, ideally through a New Zealand Government security card, is required.

- Electronic devices are not permitted within Pipitea House and will need to be locked away in a room behind reception.

15 Key response plans are listed in theAnnexes

Security clearances

- Events that involve discussion of classified information will require staff attending ODESC or Watch Group to hold the appropriate security classification. DPMC (NSS Directorate) will advise if a clearance is required when calling the meeting. It is up to agencies to ensure that their attendee holds the appropriate clearance level.

- For the majority of non-security issues, the classification will be at RESTRICTED. Incidents should be managed at the lowest possible classification to enable early and effective dissemination of critical information to all responders in order to mitigate the impact.

- Names of those attending meetings must be provided in advance if at all possible. If a Watch Group or ODESC will include a classified discussion, confirmation of security clearances will also be required from the agency. In such cases, an approved government identity card is to be worn at meetings if available.

National Crisis Management Centre (NCMC)

- The National Crisis Management Centre (NCMC) provides a secure, centralised facility for:

- • Information gathering, management and sharing;

- • Coordinating and directing response operations, planning and support;

- • Liaison between the operational response and the national strategic response;

- • Strategic level oversight and decision-making;

- • Issuing public information and conducting media liaison;

- • Supporting the Prime Minister, Ministers and Cabinet;

- • Coordinating and managing national resources and international assistance (if required).

- In a response to a major crisis that involves the activation of the National Security System, it is expected that the all-of-government response, led by the lead agency, will operate out of the NCMC.16

- Key CIMS17 positions, including the Controller, will be filled by the lead agency. Other CIMS positions, including function managers if appropriate, can be filled by staff from other agencies. In addition, agencies may be requested to provide liaison officers at an appropriate level.

- The NCMC will be expected to produce a situational report and action plan focusing at the strategic level and encompassing all government considerations, not simply those of the lead agency. This should usually include consideration of the economic, environmental and/or social impacts, issues pertaining to maintenance of the rule of law and integrity of the state, and implications for New Zealand’s international relationships.

16 The function and operation of the NCMC is currently being reviewed (July 2016).

17 Information on CIMS can be found at www.civildefence.govt.nz. See paragraph 56 for discussion of the intersection between ODESC and CIMS.

Accessing the NCMC

- The NCMC is located in the basement level of the Executive Wing of Parliament (the Beehive). There are two entrances to the parliamentary complex; the main entrance to Parliament (known as the Executive Wing) and one in Bowen House 70-84, Lambton Quay. The NCMC can be reached through either of these entrances. To access the NCMC itself, officials must be escorted by someone who holds a parliamentary access card. When the NCMC is activated, officials will be advised as part of the activation process how their access into the NCMC will be facilitated.

- For some events, temporary access cards to the NCMC can be issued. This can be arranged through DPMC NSS Directorate or the Ministry of Civil Defence & Emergency Management.

- During business as usual, the primary NCMC contact is the Ministry of Civil Defence & Emergency Management’s Operations Team.

Supporting Ministers

- In situations involving national security, particularly if there is a significant and/or imminent threat, the support that must be provided to the Prime Minister and other responsible Ministers is paramount. The principles which guide the support to Ministers include:

- All efforts must be made to avoid surprises: brief early and update regularly;

- The Chair of ODESC is the formal interface with Ministers, as the voice of ODESC which acts as the coordinating entity for consideration of Ministers’ needs with respect to the response, and for operationalising Ministers’ expectations;

- DPMC will liaise with the Prime Minister and the Prime Minister’s Office;

- Lines of communication between individual Ministers and their departments will be maintained and operate as they usually do;

- Ministers can be expected to robustly challenge plans, assumptions and judgments as part of their assurance process. It should not surprise or alarm officials when this happens.